Coming Up

Jan 18 @ plus de vin – ferment. paint EMILIA ROMAGNA / taste a rainbow of frizzante, rifermentato, + other alt sparkling 🌓 [tickets]

Jan 21 @ with.others – over the mountain. color ALPINE WINES / explore how a landscape can show up in a glass. what does a place make a wine taste like? 🌘[tickets]

Feb 8 @ plus de vin – community. paint BURGENLAND / how does a wine region come into being? why are some bottles more expensive than others? how do I read a wine list? 🌗 [tickets]

This is the third part of a 6-part series about time travel, wine histories, and the bottles of the fall/winter 2025 club shipment.

Hi folks,

‘Chilled red’ is a category that kind of slips through your fingers. It’s hard to look at dead on, and hard to talk about. It does not attract the same flurry of discourse and scorn that orange wine does, despite in some ways being its trend replacement. (Chilled red somehow manages to absorb rosé and displace orange. It’s capacious!)

It’s capacious, too, in that unlike orange or pink, ‘chilled’ is a service point, not a winemaking approach. Listen: I understand that some red wines are going to taste better colder than others. But there’s no stable category here. Service temperature is just a dial you can spin, like equalizer settings on a stereo. “Do you have a chilled red?” guests ask me behind the bar, and part of me thinks give me a cambro, five minutes and a salt brine solution and I’ll have as many as you want.

(I’ve at times poured a wine by the glass — like say, Derek Trowbridge’s “Impulse” co-ferment of regeneratively farmed merlot and chardonnay — that can perform double duty if asked. At 50 degrees or so, it’s a refreshing summertime patio pounder. Take it up to the high sixties, and it’s suddenly plummy, velvety, making that lost cabernet drinker happy.)

That’s just to say, any red is a chilled red if you try hard enough.

And trend aside, little nuances of service aside, whether or not you’re putting it into a conceptual bucket called “chilled red,” you probably do want to pop that bottle into the fridge at home before you drink it. It’s going to be tastier! If you’re running a bar or restaurant, your big (often neglected) operational crux is going to be how to keep the red wines you’re pouring in that 55–65 degree sweet spot.

Tens of tens of thousands of bottles of red wine are sitting all over the country out on counters, the temperature of lukewarm soup, in airport bars and chain restaurants and yacht clubs and New American bistros with Wine Spectator awards of excellence, crying out to be chilly enough to need a sweater. (This is far from a revolutionary point but if it results in even one additional bottle of red wine being served at cellar temperature, repeating it will have been worth it.)

But what else is going on here?

In some ways, it might just be that ‘chilled red’ has shed the generational sangria / wine cooler / cheap Chianti stigma that was kicking around in the ‘70s and ‘80s. People have remembered that it’s refreshing to drink refreshing things at a cookout. (Nothing sounds more exhausting than pairing your hot dog with an 80 degree malbec.)

There’s that broader food culture move towards acidity, vinegar, vegetables, crunch, delicacy — and away (also generationally, maybe?) from some of the maximalist WINE FLAVOR that was happening in the Parker era .

“Chilled red” is also easy to say, for sure, and that’s always kind of important, like when we’re talking about a grape like barbera or a place like Sancerre. It doesn’t sound too weird or elevated and, unlike orange wine, won’t raise alarm bells with your natural wine haters / skeptics.

And that’s crucial, because I think part of it, maybe the biggest part structurally, has to do with the growth and mainstreaming of the natural wine movement.

Here’s what I mean — I’ll try to be quick:

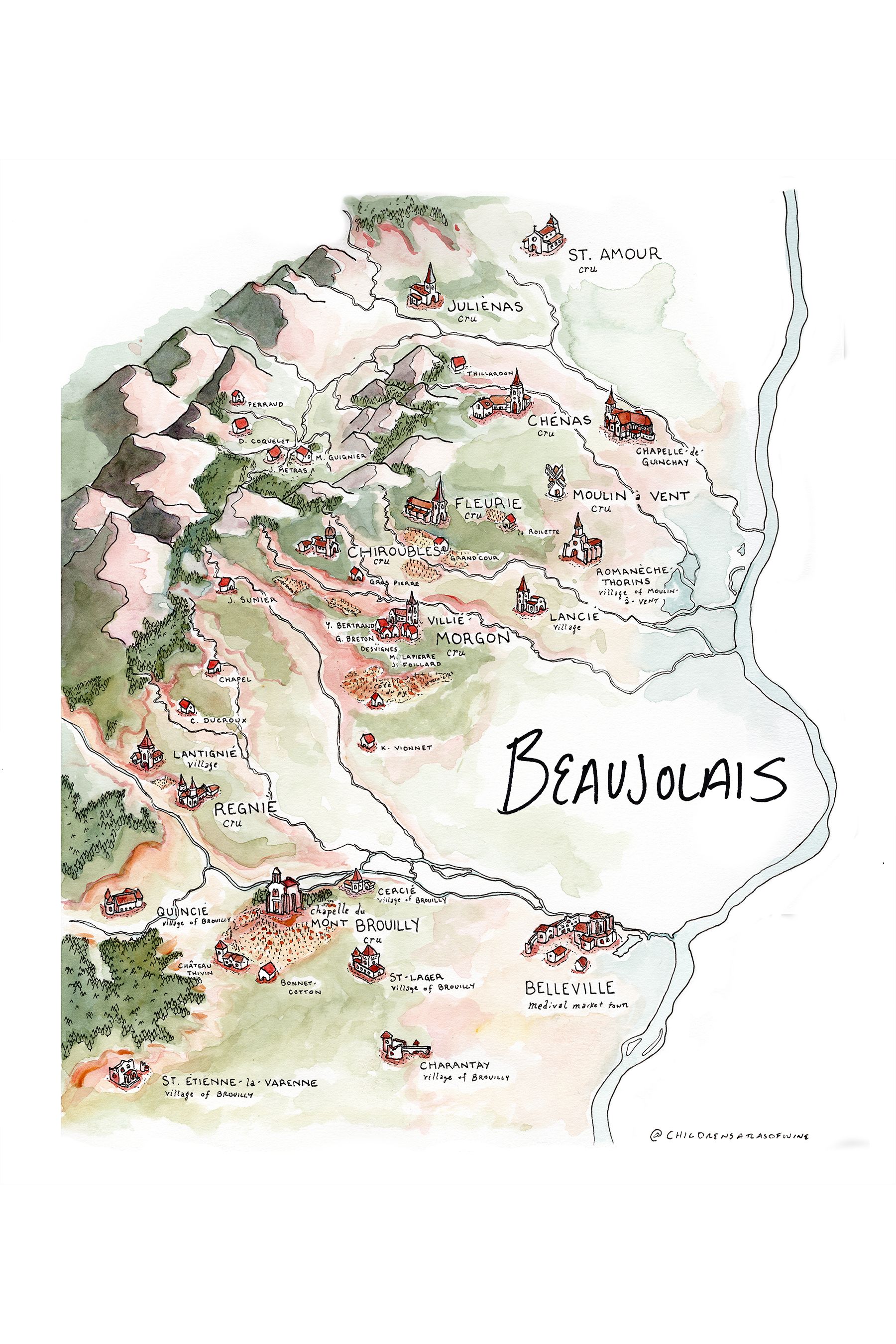

A short history of why Beaujolais = natural wine

(Do you want a version of this that’s a walk-and-talk video? Scroll to the bottom of hte page.)

French natural wine was born in Beaujolais as a reaction to the region’s industrialization. (Natural wine movements grow in the heart of places worst affected by the transformation of vinegrowing places into factory floors: Emilia, Penedès, Anjou, the Languedoc, Itata....)

Jules Chauvet (b. 1907), a Beaujolais merchant and taster trying to solve a problem of stalled and reduced ferments dogging the whole region, figures two things out:

One — carbonic maceration, a fairly technical approach developed in the ‘30s that involves blanketing whole uncrushed clusters with inert gas to encourage a no-oxygen ferment in the berries itself (at night it sounds like rice krispies crackling in milk), could get around some of the problems they were having with their nutrient-starved, gross-smelling fermentations and make it easier to make wine without additives. (Wines made via this process also have a gentle, juicy extract and a lively, fruity-floral aromatic profile. Bonus!)

Two — the root of the problem was farming itself: the herbicides, synthetic pesticides and chemical fertilizers that the postwar era had made ubiquitous had also turned the soils of Beaujolais into a wasteland, inert and unable to support healthy microbial life, and that’s why the ferments were fucked in the first place. Fix your heart, change your farming, save your wine.

Chauvet meets a young Marcel Lapierre, still working conventionally, in 1981, and takes him under his wing. Because Lapierre is a charismatic figure who tends to fit an entire world into his living room at any given time, the farming approach and the style approach spread together in tandem. Folks all over the place cite their first bottle of Lapierre as the reason they started making natural wine of their own. Light, often semi-carbonic reds called 'gulpable’ in French onomatopoeia (glou-glou) become basically synonymous with “wine made by natural winemakers” — even though, of course, people could (and did) make all kinds of other things in hands-off ways, everything from big, port-y late harvest reds to frothy bubbles to whites like springwater, and beyond.1

In parallel, conventional Beaujolais producers figured out that carbonic , dry active yeast, and other winemaking tricks let them do an end run around the farming problem. Keep using all of the chemicals you want, boys!

Lalvin 71B, a dried active yeast strain that lends fruit, banana laffy-taffy flavor, was isolated at the National Institute for Agriculture Research in Narbonne in 1971. Now you could add yeast, not just to cultivate predictable fermentations and push them to finish, but to create designer aromatic profiles. After a decade of run-up, Beaujolais Nouveau, a fresh and fruity confection built around full carbonic, the juicy juicy smell of Lalvin 71B, and filtration to allow bottling in time for Thanksgiving, hit the U.S. in 1982 and became a commercial sensation. Talk about a chilled red!

Today, somewhere between a third and a half of Beaujolais’ entire production remains Nouveau, even though everybody I talk to under the age of 30 has never heard of the stuff.

And even though a lot of American wine professionals’ first Beaujolais will have been wine made naturally and farmed organically from one of the region’s icons, the rate of organic farming still lags behind the (already low) French national average. It’s not to say that nothing has changed (we’re seeing big generational turnover, outside investment from Burgundy domaines, all kinds of movement), but the industrial structures that have shaped the region for a hundred years are still in place, warping the hillsides around them like neutron stars.

Inventing (chilled) red

Pulling back a little bit, reddish wine made for refreshment with a light touch was kind of the only way red came for a long, long time.

In the middle ages, white wine or coppery rosé is the preferred beverage of prelates and princes. The peasantry, at least in places that can grow vines, are drinking pale red low-abv piquette: pressed grapeskins rehydrated with water, honey, maybe some herbs and spices — medieval wine coolers.

In 1224’s “The Battle of Wines”, the Norman poet Henry d'Andeli recounts a tasting of 70 white wines from across Europe judged by a drunk English priest in the court of the French king. The priest commends the good and excommunicates the bad. A red wine is chased from the room for causing flatulence. Every other wine in the lineup is white. A wine from Cyprus, likely sweet and dried on straw mats, is crowned "apostle, who shone like a star."

It will be another 600 years or so before wine is deliberately aged in glass bottles sealed with cork in order to soften it and evolve its aromas,3 which means that it will be another 600 years or so before ‘traditional red wine’ a la Barolo and Bordeaux (long macerations, raising in oak before bottling, clarified with egg whites) gets invented.

‘Red’ wines in the meantime are most often reddish pink, often a short maceration (like a dark rosé) or co-fermented with white grapes, in styles that have a rainbow of regional names, from the cherry-colored cerasuolo in Abruzzo to clarete in Rioja to Franken’s rotling (little red) to ryšák (ginger-haired) in Moravia and western Slovakia. Nebbiolo (before the invention of Barolo) is most often pink and lightly fizzing.

These wines don’t have a particularly elevated reputation. The association is with the working class, sour light brightness, cheap volume. Aristocrats and cultural philosophers were not writing paens to the crushable co-ferments of the 1890s. In 1976, Chianti’s new DOC mandated the inclusion of 30% white grapes, and today this is often talked about as a way to pass off inferior trebbiano toscano that had been planted in the postwar for bulk production and hide it in the blend. 100% sangiovese was seen as a move towards purity and improvement.

But it would be just as true to say that here, historically, co-fermentation was part of the patrimony, just like it was basically everywhere.

And now? You can always count on the next trend pieces being for new things that are very old.

Juicy co-ferments of red and white grapes have been kicking around the Paris natural wine bar scene as blouge (a cutesy mash-up of blanc et rouge that I think is frankly silly, but ymmv). I don’t know if blouge is going to catch on over here (although I found at least one social media explainer), but I’ve been using “co-ferment” for this category right next to my orange and chilled reds for 3–4 years and you’d be shocked by how little confusion (or even follow-up questions) I field.2

Sneaking rosé into your glass

For now, the most likely way I’m selling interesting, non-commodity rosé is by putting it into the glass of chilled red drinkers.

It’s the same one-two shuffle as when I’d move orange wine lovers into an unfortified palomino or a chenin on schist. The pleasure – temperature – context calculus is more or less the same, it’s just a color they don’t think about and rarely taste a good version of.

Here, I also get to have my history cake and eat it too by throwing a little Georgian wine into the mix, and in a more delicate vein than the deep amber rkatsiteli and opaque purple saperavi that still dominates people’s impressions of what qvevri wine can be. This is Jane Okruashvili, who makes wine with her brother in a little marani up in the eastern fortress city of Sighnaghi.

The grape is tavkveri, an old Kartli variety that — unusually — can’t self-pollinate. (Most domesticated vines are intersex, having both male and female parts, which only occurs in about 5% of wild vinifera. Tavkveri is female alone, and needs to be planted alongside other vines.)

Vigorous, high-yielding, big-berried, tavkveri often used for rosé (as here) as well as lighter reds that are, you guessed it….

“wine snobs may turn up their noses at the very idea”…”chilled red wine used to feel controversial”…”while it may feel like breaking the time-honored tradition”…”take some risks”…”you remember that aunt?…turns out she was on to something”

Write back with your most transgressive and risky chilled red stories!

Talk soon,

<3,

grape kid

Not everybody can afford a package of wine shipped across the country, but if you’d like to support more work like this you can buy us a cup of coffee via our Patreon.

Coming next time: Pt. 4 American wine

1 Kermit Lynch brings Marcel Lapierre’s wines into the US market for the first time in 1991. The February store newsletter lists the ‘89 Morgon for $13.95 — about $30 in today’s dollars. A bottle of current release Morgon from Lapierre (now his children Mathieu and Camille) will run you about $52. Beaujolais is expensive these days!

2 (From the tech sheet for Gulp Hablo Fresco, the Gulp Hablo chilled red brand extension launched in 2024: “Gulp Hablo Fresco is a wine that looks back at the roots of Spanish wines, when viticultors would plant red and white grapes together, ferment them together, and release them as fresh as possible.”)

3 eventually giving us the infuriating distinction between “aroma” and “bouquet,” as well as words like “tertiary”

@childrensatlasofwine Sunday afternoon 10.12 @ plus de vin in BK thanks Vine Wine for the fancy Beaujolais #childrensatlasofwine